Translate this page into:

Through the Murky Waters of “Web-based Orthodontics,” Can Evidence Navigate the Ship?

Address for correspondence: Prof. Nikhilesh Vaid, Department of Orthodontics, European University Dental College, Dubai Healthcare City, Dubai, UAE. E-mail: orthonik@gmail.com

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Orthodontists at this point globally, are witnessing a time in history when the practice of orthodontics is gradually transforming itself from analog, paper, alginate, and plaster mode to digital, paperless, three-dimensional scans, and technologically-savvy mode.[1,2] For better or worse, more than technological innovations in orthodontics, the advent of the worldwide web or the Internet has been a significant disruptor for orthodontic care. The Cambridge dictionary defines disruptor as “a person or thing that prevents something, especially a system, process, or event, from continuing as usual or as expected.”[3] Patients today get orthodontic appliances delivered at their doorstep, have their progress monitored with a smartphone app and order retainers on treatment completion without ever having to step into an orthodontist’s office. Turpin and Huang have said orthodontics has passed through the “age of expert,” “age of education,” “age of science,” and is currently, said to be in the “age of evidence.”[4] In recent times, however, the ever-increasing penetration, reach, and usage of the Internet have popularized newer, alternative modalities of orthodontic treatment among masses, and seem to have ushered in the era of the “dot-com patient” and “web-based orthodontics.” This has also given rise to certain contemporary sub-phenomena in orthodontics; unique to the times we are living in. These are discussed as follows:

YouTube-based Orthodontics

YouTube videos such as “make your own braces,” “make your own fake braces,” “how to make your fake braces look real,” and “how to close gaps using rubber bands” etc, advocating Do-it-Yourself (DIY) orthodontics, have been the source of orthodontic crash courses in ruining teeth for many.[5] DIY braces are not a concern because of the threat they pose to orthodontics, but because most of these videos are predominantly made by children for children. This trend is notorious due to the serious hazards posed by the unscrupulous, thoughtless, childish, and potentially dangerous use of rubber bands and things such as back-stopper of earrings made of materials with high-nickel content and indiscriminately sticking (with possibly toxic glues or adhesives) or wearing them inside the mouth for long periods of time.[6] A recent survey among members of American Association of Orthodontists reported that the age of people attempting to fix their own teeth ranged from as young as 8 years to as old as 60 years and approximately 70% of these DIY patients seen by orthodontists belonged to a social media-friendly age group, between the ages 10 and 34. Social media usage in these age groups exceeded 80%.[7]

If one is not industrious enough to make them on their own, a vast array of fake braces are available for purchase, sold widely on Facebook, Instagram, and twitter, as fashion items or accessories, catering to those who aspire to achieve the fashion-icon or social-status associated with wearing braces among their peers. This problem is widely prevalent in Southeast Asian countries such as Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Philippines. Professional bodies[8] and government authorities[9] likewise have condemned such practices and issued public safety advisories.

This category of You-tube-based orthodontics also includes laypeople sticking brackets and providing supposed orthodontic treatment in houses, spas, or hotel rooms, having no formal education in dentistry whatsoever and have trained themselves by exclusively watching such videos. To avoid detection and arrests they are even known to shift locations of their activities and move from one place to the other. The bracket materials and adhesives used are neither medical grade nor suitable for intraoral use, and have been reported to be toxic and unsafe. The risks of them spreading serious infections through cross contamination are enormous and so are other serious adverse effects of moving teeth without proper technique or knowledge such as root exposure, fenestration, dehiscence, and avulsion. The “treatment strategy” or modus operandi of such people mostly is to just stick the brackets and take the money, after which the patients are on their own. Fake contraptions that look like braces but have no slots and are not really brackets are easy to detect as fake. Brackets used by such unscrupulous practitioners often have slots and they insert some wire and use some form of elastic chains to secure them in the slot. In such cases, it is difficult for patients themselves or subsequent orthodontists who see them to differentiate them as fake, on a cursory look. The reality is only discovered when the patient reveals the history of the manner in which treatment was delivered, where and by whom. Awareness among consumers regarding the modus operandi is being created through news and media, yet people continue to fall prey to the apparently “cheap and easy” options, which prove expensive in the long term, considering the damage caused to health, oral tissues, and occlusion.[10]

Facebook-based Orthodontics

The evidence pyramid depicts the hierarchy of evidence, with expert opinion being at the lowest level of the pyramid and systematic reviews and meta-analysis at the highest. In a recent blogpost, Dr. O’Brien, cautioned about the emergence of a new lowest level of evidence – Facebook-based Orthodontics” – based on the multiple opinions provided by Facebook users![11] A popular phenomenon is the widespread use of social media posts by practitioners to exhibit and discuss their cases. Practitioners may consider this as a good way to showcase their best cherry-picked cases and promote their practice; however, the inevitable discussions that accompany such posts may or may not be illuminating, to say the least. In the absence of objective analysis, subjective, individual opinions based on their forcefulness, or persistence may dominate such discussion threads. We have personally been privy to discussions on such posts where self-proclaimed experts who have been propagating a treatment philosophy (that they refuse to even attempt to publish in peer-reviewed literature for decades together) opine on patient pictures using academic titles that they simply do not possess. The more experienced and informed clinicians may escape the sway of such statements by “Facebook orthodontic warriors” on social media, by relying on their experience and learned scientific facts; however, the less-informed clinicians or freshly passed out graduates may fall prey to inaccuracies, fallacies, misleading case presentations and false imagery. It is important to educate that those opinions expressed on Facebook, Wikipedia, and other social media posts are not the best sources of clinical evidence. These same social media platforms on the other hand can be harnessed to create awareness and disseminate objective facts and evidence-based information.[11]

Manufacturer-based Orthodontics

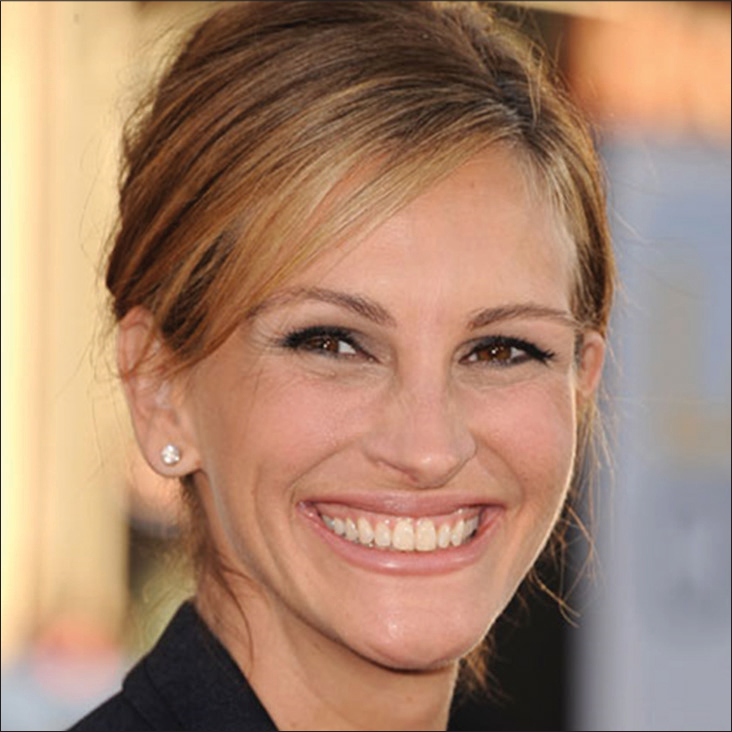

The Internet has had the effect of opening up markets and possibilities both for orthodontic product manufacturing companies and for non-orthodontists wanting to practice orthodontics. To reach a wider audience and maximize revenue generation, the strategy of orthodontic companies is to not restrict them to catering to the orthodontist niche alone. In their goals to expand their scope, they harness the non-orthodontists as well to augment their sale numbers. This has resulted in the propagation of an easy-to-follow philosophy by manufacturers and their proponents. They over-simplify orthodontic treatment and make it seem deceptively simple, so that it appears reassuringly easy, manageable, and doable to even those not qualified or trained in orthodontics. This explains the active promotion of “expansion,” “nonextraction”, or “arch development” methods of treatment irrespective of case suitability, since extraction mechanics are too complex and time-consuming for “good marketing.” Expansion and nonextraction treatment strategies are valid and necessary tools in an orthodontist’s treatment plan armamentarium, and like any other treatment modality they should be applied wisely in suitable cases and are not to be considered as the only moot point in orthodontics. One practitioner during an aligner workshop was narrating how their adult patient was unhappy after treatment was completed by expanding of arches because they felt their smile was too “toothy” and “broad.” The practitioner proudly explained that they managed to convince the patient to accept their smile by saying “Look at Julia Roberts… she also has a broad toothy smile like you… she looks so good… so be happy that you have a smile like Julia Roberts! [Figure 1]”

- The much admired smile of Hollywood actress Julia Roberts

There is but only one Julia Roberts and trying to force her smile on someone not like her is not really giving the patient the best they can or should get [Figures 2 and 3]! They seem to forget “create the smile that is best for the patient, and not the one that best suits your practice!” This displays a lack of respect for the patient’s individuality or concerns and happens when practitioners are reluctant to focus on the patients’ needs, thereby imposing their idea of beauty on the patients. This is because they are indoctrinated to dogmatic cults in orthodontics that stick to a predecided method of treatment for all cases. This is known as the “law of instrument” or “Maslow’s hammer” which states, “If the only tool you have is a hammer, you treat everything as if it were a nail.” The law alludes to the cognitive bias that involves an overreliance on a familiar tool, thus it is with those who choose expansion for patients not because it is the best thing to do but because either that is the only tool in their armamentarium or the one they are most “comfortable” with. There are many fear mongering, conspiracy theory fueled websites spreading false information to discredit orthodontic extractions. Such sites play into the narratives of groups with vested commercial interests who seek to exploit the fear and ignorance of consumers.

- A photoshopped image (freely available on the Internet) of Hollywood actress Kristen Stewart’s face fitted with Julia Robert’s smile!

- The beautiful original, unedited face and smile of Hollywood actress Kristen Stewart

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Priti Mulimani1,2, Nikhilesh Vaid3

1Associate Professor and Chair, 2Department of Orthodontics, Melaka-Manipal Medical College, Melaka, Malaysia, 3Visiting Professor, Department of Orthodontics, European University Dental College, Dubai Healthcare City, Dubai, UAE

Address for correspondence: Prof. Nikhilesh Vaid, Department of Orthodontics, European University Dental College, Dubai Healthcare City, Dubai, UAE. E-mail: orthonik@gmail.com

References

- Up in the air: Orthodontic technology unplugged! APOS Trends Orthod. 2017;7:1-5. Available from: http://www.apospublications.com/text.asp?2017/7/1/1/199178. [Last accessed on 2017 Aug 31]

- [Google Scholar]

- Digital workflows in contemporary orthodontics. APOS Trends Orthod. 2017;7:12-8. Available from: http://www.apospublications.com/text.asp?2017/7/1/12/199180. [Last accessed on 2017 Aug 31]

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Disruptor. Available from: http://www.dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/disruptor. [Last accessed on 2017 Aug 29]

- Searching for evidence in clinical practice In: Graber LW, Vanarsdall RL, Vig KWL, eds. Orthodontics: Current Principles and Techniques (5th ed). Elsevier, Mosby; 2011.

- [Google Scholar]

- Commoditizing orthodontics: “Being as good as your dumbest competitor?”. APOS Trends Orthod. 2016;6:121-2. Available from: http://www.apospublications.com/text.asp?2016/6/3/121/183154. [Last accessed on 2017 Aug 31]

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- DIY Braces. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K0Bsx5S7L-g. [Last accessed on 2017 Aug 29]

- [Google Scholar]

- Orthodontists Report Uptick in Number of Patients Attempting DIY Teeth Straightening. Available from: https://www.mylifemysmile.org/press-room/orthodontists-report-uptick-in-number-of-patients-attempting-diy-teeth-straightening. [Last accessed on 2017 Aug 29]

- Consumer alert on the use of elastics as “gap bands”. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2014;146:271-2.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fake Braces. Available from: http://www.myhealth.gov.my/en/fake-braces-2/. [Last accessed on 2017 Aug 29]

- [Google Scholar]

- Malaysia’s MOH Warns against Obtaining Fake Braces from Illegal Dental Practitioners. Available from: https://www.today.mims.com/topic/malaysia-s-moh-warns-against-obtaining-fake-braces-from-illegal-dental-practitioners. [Last accessed on 2017 Aug 29]

- [Google Scholar]

- Facebook Based Orthodontics. Available from: http://www.kevinobrienorthoblog.com/facebook-based-orthodontics/. [Last accessed on 2017 Aug 29]

- [Google Scholar]

- Evidence-based practice and the evidence pyramid: A 21st century orthodontic odyssey. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2017;152:1-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evidence based medicine: What it is and what it isn’t. Br Med J. 1996;312:71.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- An orthodontic registry: Producing evidence from existing resources. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2017;152:289-91. Available from: http://www.ajodo.org/article/S0889-5406(17)30540-1/fulltext. [Last accessed on 2017 Aug 31]

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]