Translate this page into:

Impact of SARS-CoV-2 on orthodontic education and global practice guidance: A scoping review

*Corresponding author: Dr. Snehlata Oberoi, Department of Orofacial Sciences, School of Dentistry, University of California, San Francisco, California, United States. sneha.oberoi@ucsf.edu

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Azizollahi R, Mohajerani N, Kau CH, Fang M, Oberoi S. Impact of SARS-CoV-2 on orthodontic education and global practice guidance: A scoping review. APOS Trends Orthod 2020;10(2):78-88.

Abstract

The acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), also known as COVID-19, has had unprecedented impact on orthodontic care and education. Dental schools and clinics have stopped their normal educational and clinical activities worldwide, while only accepting emergency cases. It is still unknown when students will return to clinics to resume patient care and receive training. This scoping review aims to examine, summarize, and reference current resources to analyze the impact of SARSCoV-2 on orthodontic practice recommendations and orthodontic education. This review summarizes recommended global guidelines to provide a better understanding of the current consensus for protocols of safe orthodontic care; this scoping review serves to help create concrete guidelines for orthodontists to deal with the current SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, and for future infectious diseases, and assessing the impact on orthodontic education. Using inclusion/exclusion criteria, 456 articles were screened by two independent screeners and data were extracted and charted from 50 relevant sources. These 50 sources conveyed similar guidelines for provider and patient safety in orthodontic practices, with some stressing certain protocols such as personal protective equipment over others. Impacts on orthodontic education conveyed changes in protocols for learning, competency, and clinical skills. As this respiratory illness progresses, the field of orthodontics needs cohesive universal clinical guidelines and further assessment of the impacts of SARS-CoV-2 on orthodontic education.

Keywords

SARS-CoV-2

COVID-19

Coronavirus

Orthodontics

Education

BACKGROUND

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has been considered to have an epicenter in the Wuhan, Hubei province of China in late 2019. It has been deemed a zoonotic particle originating from horseshoe bats and transmitted to humans through unknown intermediaries; however, recent testing speculates pangolins and snakes to be the intermediate link. SARS-CoV-2 is transmitted through inhalation and through direct contact with droplets;[1] through travel, the disease has spread worldwide and has resulted in over 104,000 deaths in the United States and over 362,000,000 deaths worldwide as of May 29, 2020.[2] The perilous nature of this illness resulted in the declaration of a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) on March 11, 2020.[3] It has been deemed that asymptomatic carriers can transmit the disease, thereby, adding to the infectious capability.[1,4] SARS-CoV-2 primarily affects the upper respiratory tract with a range of symptoms from mild, like the common cold to severe, like pneumonia.[5]

This respiratory illness is not only resulting in a large death toll but also having implications in various sectors, major ones being dentistry and education. All dental professionals, including orthodontists, are at risk due to this disease, as SARS-CoV-2 particles have been identified in saliva.[6-8] Aerosols from salivary fluids created during dental procedures can facilitate transmission.[9] Many schools have been shut down in efforts to attenuate transmission. This scoping review investigates the rapidly evolving situation surrounding SARS-CoV-2, in particular, the consequences of SARS-CoV-2 on orthodontic education, and the global guidelines recommended to orthodontists to tackle transmission in practice.

The scoping review framework provides a broad starting point for the impacts; SARS-CoV-2 will have on orthodontic education and global guidelines, as it is a currently unveiling disease. Systematic reviews follow a more well-defined question and require a narrower bank of studies assessed for quality; this leaves most systematic reviews as inconclusive. Orthodontics has been a slow adopter of the scoping review framework, but this framework can provide a solidified foundation for further, more detailed investigation into the impacts of SARS-CoV-2.[10] It may be useful to make use of reviews on orthodontic technologies such as The Last Decade in Orthodontics: A Scoping Review of the hits, misses, and the near misses! to analyze the integration of technology before SARS-CoV-2 for comparison to determine how guidelines and technological integration have changed in clinical practice and education after the pandemic.[11] It will also be useful to move toward a telehealth perspective with innovative appliances such as Bluetooth-enabled retainers paired with mobile applications and precision technology in orthodontics to minimize provider- patient interactions per health and safety measures.[12,13]

Due to the novelty of this strain of the coronavirus, the information surrounding this illness is constantly changing based on new data and progressing research. This review is based on data and guidelines as of May 24, 2020. Please be sure to consult your respective national health organizations for up to date considerations. Because the situation surrounding SARS-CoV-2 is recent and rapidly changing, there is little concrete scientific evidence to refer to, or protocols to follow. This review is intended to analyze the implications for orthodontic education, and the protocols various worldwide orthodontic societies have recommended for orthodontists to follow.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

A scoping review was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews framework.[14]

Search strategies and data sources

In efforts to establish a thorough review, various sources have been examined, summarized, and referenced. A comprehensive search of PubMed, EMBASE, and Web of Science databases was conducted for studies published from January 2018 to May 2020. A combination of MeSH/Emtree terms and keyword searches was used to identify studies relating to the impact of SARS-CoV-2 on orthodontic practice recommendations and orthodontic education (for details, Appendix A) Additional studies are identified through searching reference list of included studies using the Web of Science. The final searches were complete on May 24, 2020. Because this is a rapidly progressing and current issue, major dental education and health organizations’ websites such as American Dental Education Association and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention were also searched for current guidelines. A search was also conducted on the World Federation of Orthodontists (WFO) website for a list of affiliate organizations. Each affiliate organization’s linked website was navigated on May 4, 2020, for information on their SARS-CoV-2 guidelines in respective countries.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

We included literature published from January 2018 through May 2020, in English language, and literature that discusses dental professionals broadly: General dentists and orthodontists only. We excluded literature aimed at specific specialties, other than orthodontics. The WFO affiliate organization orthodontic societies that did not have SARS-CoV-2 updates or guidelines on their respective pages were not included.

Screening and data extraction

Two independent reviewers screened all titles and abstracts to arrive at a bank of relevant articles. Upon discrepancy in decision to include an article, a third reviewer was consulted. A full-text review was then conducted by two reviewers to further screen the articles for inclusion. Data extracted and charted from articles included the type of study and whether or not the study discussed personal protective equipment (PPE), hand hygiene, radiograph protocols, pre-procedural interventions (e.g., mouthwash and toothbrush), waste disposal, disinfection/sterilization, ventilation, high-speed suction, single-use tools, social distancing, pre-treatment screening (e.g., telemedicine, questionnaires, and body temperature), anti-retraction handpiece, and orthodontic education impacts.

RESULTS

Search results

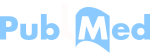

A total of 641 records were identified, 98 of which were excluded as duplicates. Title and abstract screening were performed for the remaining 543 records. A total of 452 records were excluded based on eligibility criteria, leaving 91 records for full-text assessment. After review, 32 additional records were excluded, with reasons listed in [Figure 1a], leaving 59 articles in the review. These reasons for exclusion are further defined in [Figure 1b].

- (a) Flowchart of selection criteria for manuscripts that depicts number of identified articles, inclusion and exclusion records, and flow of information throughout the reviewing process, (b) Table defining reasons for exclusion.

Characteristic of included records

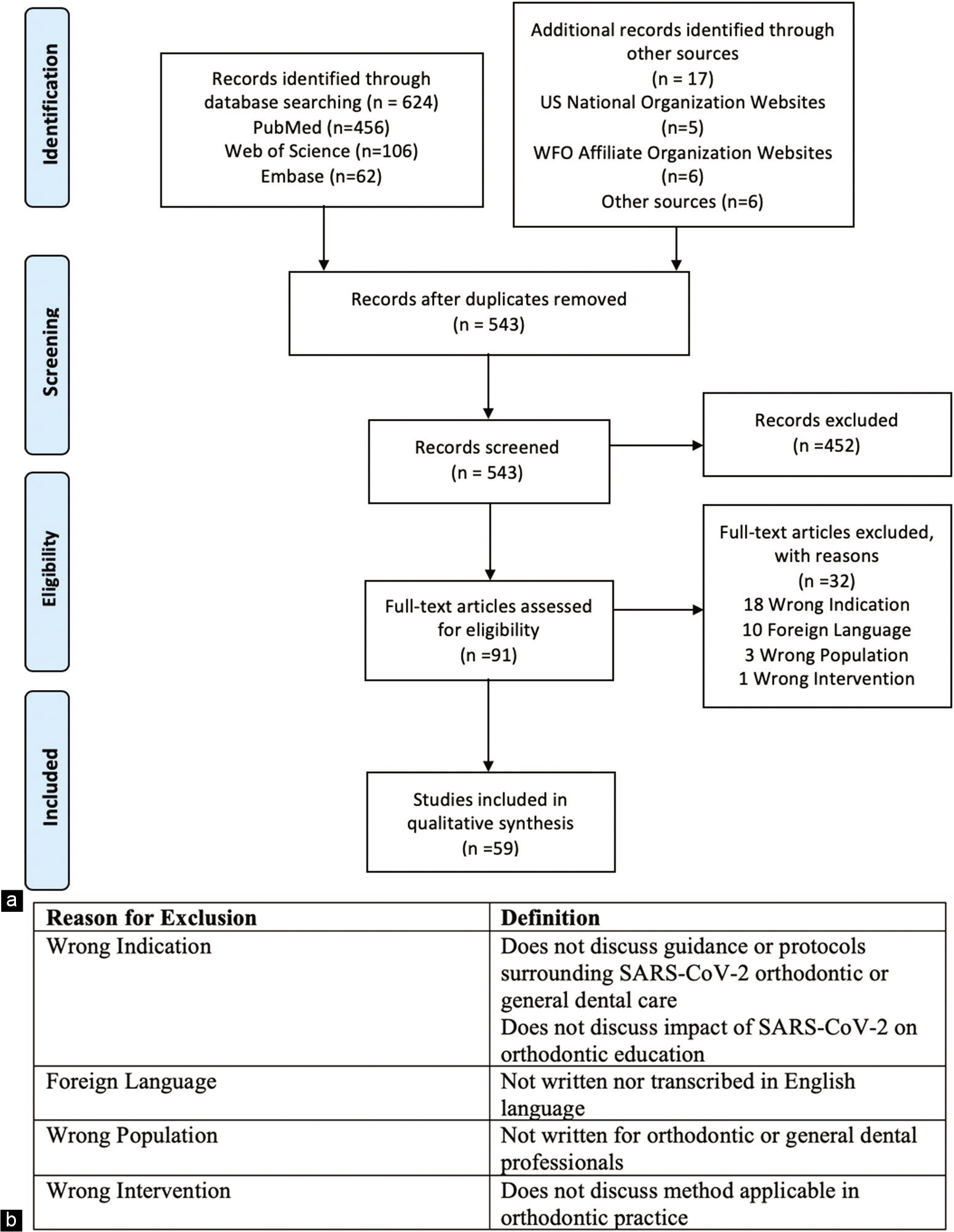

Of all the literature (n = 59) included in this scoping review, 45.8% (n = 27) were published as reviews, 25.4% (n = 15) were published as editorials, 18.6% (n = 11) were published as guidelines/guidance/recommendations, 5.1% (n = 3) were published as communications, and 3.4% (n = 2) were published as perspectives. The charting of the data extraction is shown in [Figure 2a-c].

- (a) Data extraction tables summarizing sources that referenced themes of health guidelines in orthodontic practice and orthodontic educational impact, (b) Data extraction table continued with additional sources, (c) Data extraction table continued with additional sources.

Themes

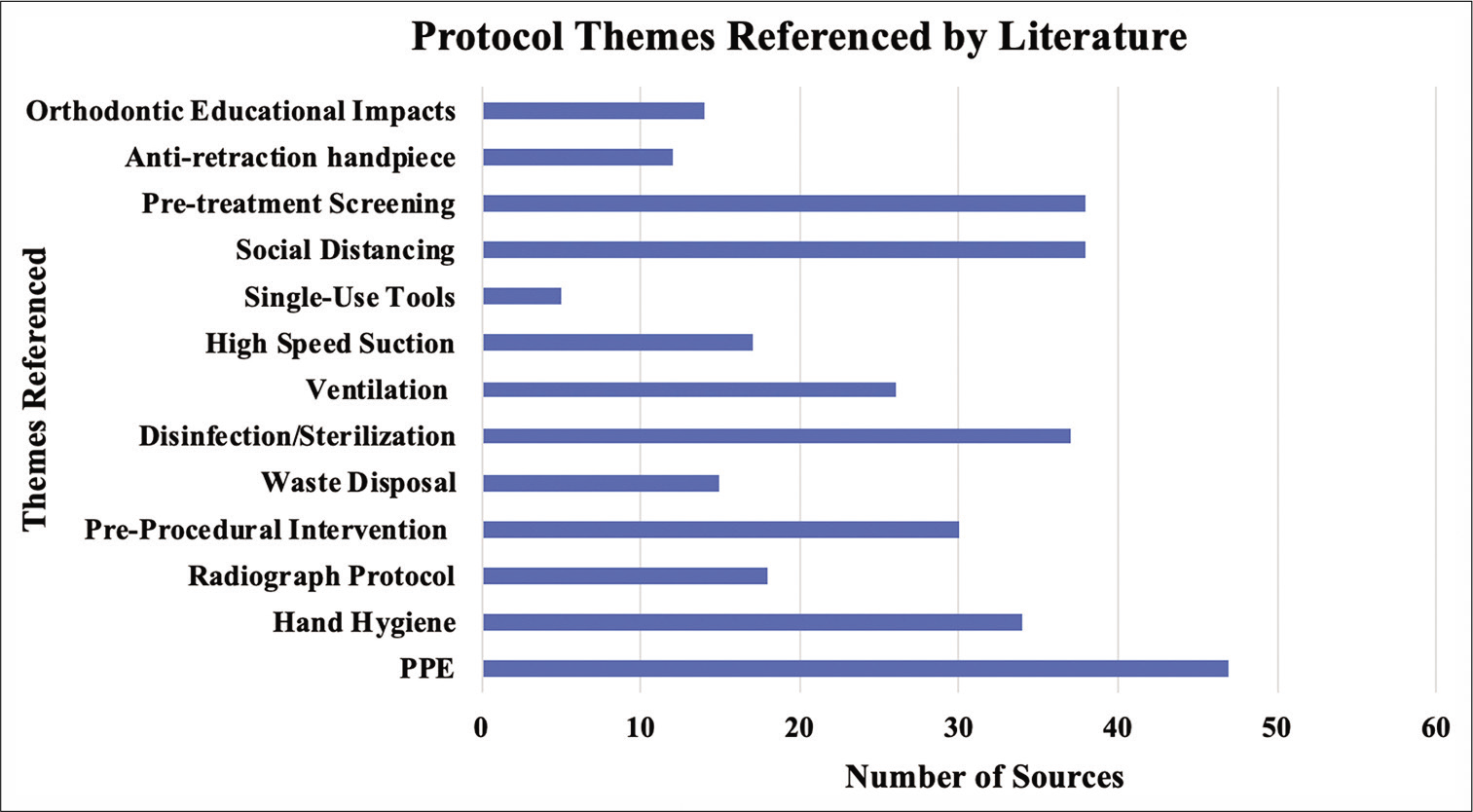

The records reviewed focused on 13 different themes identified by the independent screeners. Of the 59 records, 47 addressed PPE, 38 addressed pre-treatment screening, 38 addressed social distancing, 37 addressed disinfection/sterilization, 34 addressed hand hygiene, 30 addressed pre-procedural interventions, 26 addressed ventilation, 18 addressed radiograph protocols, 17 addressed high-speed suction use, 15 addressed waste disposal, 14 addressed orthodontic education impacts, 12 addressed anti-retraction handpieces, and 5 addressed single-use tools. This is illustrated by [Figure 3].

- Number of sources from n=59 that reference various themes of health guidelines for orthodontic practitioners and impact of SARS- CoV-2 on orthodontic education included in the scoping review.

DISCUSSION

Educational impact

Most dental education is being carried out virtually through remote learning with an unknown end date as to when normal didactic curricula may continue as health officials make decisions to strike out restrictions based on the course of the coronavirus in the respective state.[15-17] Only emergency treatments are being permitted, academic buildings being restricted, examinations and lecture materials offered virtually, and hands-on assessments delayed.[15,18] Various institutions in the United States have front loaded didactic material so upon the removal of the stay at home order, clinical and simulation experiences can continue with less classroom-based learning and more clinical learning. Case studies have been recommended as a substitute to achieve clinical education in the absence of clinic time.[19] Residents have been able to participate in telemedicine consultations under the supervision of their attending and with the permission of the patient.[20]

The Commission on Dental Accreditation (CODA) of the ADA noted flexibility in accreditation standards for orthodontic education due to interruptions SARS-CoV-2 has caused. These flexibilities include use of simulations and scenario-based learning as opposed to regular patient-based learning, as well as modification or reduction of quantitative requirements residents must meet for graduation. However, the 24-month and 3700 scheduled hours minimum requirement has no flexibility and should be met with alternate remote learning or simulation experiences.[21]

In addition, students have been stripped of the opportunity to attend rotations, externships, and conferences.[22] Board and licensure examinations have been postponed, rescheduled, or delivered by different means. In the United States, the American Board of Orthodontics is administering live online proctored written examinations with Scantron/ Examity.[23] Unfortunately, graduation ceremonies for graduating residents have also been rescheduled virtually or cancelled.[24]

Upon returning to clinic, dental professionals worldwide, including orthodontic faculty and residents, face the risk of a decreased patient population as a result of the economic tribulations, this pandemic has caused. Over 16 million individuals and counting have filed for unemployment due to the pandemic.[25] The decline in employment, and the prevailing fear of acquiring SARS-CoV-2 may translate to a decrease in patients willing to receive elective dental treatment. This becomes an issue as students will not be able to complete their clinical requirements nor obtain the experiences they need to become polished clinicians. For orthodontic residents, this will mostly impact current 1st year residents, and the incoming 1st year class as they may have a decrease in the number of cases they will be able to start. It is crucial for dental programs to formulate alternative methods to facilitate clinical learning and to evaluate proficiency.[22]

Although numerous consequences to orthodontic education have resulted, in the interim, students have been able to focus on research projects related to SARS-CoV-2.[17] There has also been a rise in unique virtual activities, both academic and non-academic, for students and faculty.[14] SARS-CoV-2 is also contributing to strengthened infection control instruction for students that will benefit the field in the event of future epidemics.[26]

Of the literature explored, 23.7% (n = 14) discussed orthodontic education impacts of SARS-CoV-2. This review serves as a call for concrete studies on the consequences and changes made for orthodontic education as a result of SARS-CoV-2.

Protocols and guidelines

The recommendation at the start of the pandemic was to suspend all routine dental care, while only providing emergency care and telehealth services.[27] Emergency care translates to procedures done to alleviate swelling, pain, bleeding, infection, and trauma.[28] In orthodontics, this may be defined as an appliance impinging on the gingiva leading to trauma, pain, or infection.[29] Simple procedures such as bonding/debonding and bracket repositioning carry risks of producing aerosols.[30]

As the infection and death rates have decreased, some clinics have reopened for routine care at reduced capacities with new protocols. It is essential that all the practitioners should adapt their practices with new recommendations to protect themselves and patients until a vaccine is developed.[31,32]

Overall, the WFO affiliated orthodontic societies seem to have a general consensus on guidelines recommended to combat transmission.

Recommendations for orthodontists providing care include:

Assessment of patient risk level[33]

Updating patients on the limited access to care due to SARS-CoV-2

-

Staying up to date with patients on treatment plans

Ensure patients have contact information necessary to reach out virtually if needed.[34]

Patients should send photographic updates to provider.[34]

HIPAA violations have been relaxed to allow for telemedicine; the American Dental Association (ADA) has also included coding and billing guidelines for teledentistry.[20,37]

Patients will need to have access to a device, internet connection, adequate lighting for a virtual examination.[20]

Mobile-based notification systems such as WhatsApp and WeChat have been shown to be the most popular messenger apps and the most usable by inexperienced audiences.[38]

Have patients sign waiver to ensure their consent to this form of communication.

Attempt to resolve issues remotely before submitting to an in-person emergency appointment.

-

Remind patients to maintain good hand hygiene upon using orthodontic appliances.[38]

-

Proper use of PPE: Mask, eye protection, gown, hair covers, full face shield, shoe cover, gloves, and hazardous materials suit if available.[5]

well patient: non-aerosol procedures: surgical mask; highly recommended to use a filtering facepiece respirators (FFR) such as N-95.[40]

well or suspected/confirmed SARS-CoV-2 patient: non-aerosol or non-aerosol producing procedures: NIOSH-certified disposable N-95 FFR or better (e.g., R95, P95).

-

Providers should acknowledge that surgical masks do not provide the same level of protection as a tight-fitting N-95 mask.

Change masks between patients and during treatment if mask becomes wet.[41]

-

Face shields.

Should be tight fitting.

If reusable, should be properly disinfected, and not have any sponges or pins attached.

Best thickness is 150–200 μ for repeated use durability.

Never touch front of face shield.

Remove using gloves, then disinfect if reusable.[43]

Employers should provide long sleeve gowns, if not possible, laundry services should be provided.

All skin should be covered.[44]

-

A donning and doffing supervisor is recommended and if not possible, a buddy system should be installed to ensure providers are practicing proper infection control while donning and doffing PPE.[4]

Donning PPE: (1) Hand hygiene, (2) gown, (3) mask/respirator, (4) goggles and face shield, (5) hand hygiene, (6) gloves, (7) enter patient room

Doffing PPE: (1) Remove gloves, (2) remove gown, (3) exit patient room, (4) hand hygiene, (5) remove face shield and goggles, (6) Remove mask/respirator, (7) hand hygiene.[41]

-

Screen patients virtually to ensure they do not have symptoms and have not been in contact with an infected individual or have travelled in the past 14 days.[45]

Consider as potential carrier for 30 days after a positive laboratory test.[46]

-

Screening for temperature and symptoms upon arrival to emergency visits.

-

Consider adequate room ventilation, air purifying system, or airborne infection isolation rooms with negative suction to reduce risk of transmission.[48]

6 ACH (air exchanges/hour) minimum recommended.

12 ACH is best.

HEPA filter.

High-volume evacuator is an more inexpensive alternative.[49]

Humidity 40–60%.

Ultraviolet germicidal irradiation of 254 nm.

Barriers: Hang plastic sheet or room dividers or use private room.

-

Use of 1.5% hydrogen peroxide or 0.2% povidone pre- procedural mouth rinse as precautionary measure.[5,45]

-

Impressions should be completely disinfected by intermediate-level disinfectant.

Impressions should be proper size to prevent coughing and gagging; for sensitive patients, anesthetizing the oral mucosa of the throat is recommended before performing an impression.[8]

-

Avoid procedures that produce aerosols: Virus particles may remain in surrounding air for up to 3 h and on plastic and stainless steel services for over 72 h.[50]

Make use of single-use tools such as mouth mirrors and blood pressure cuffs.[52]

Equipment should be covered with disposable barriers.[53]

-

Radiographs should be deferred.

Nitrous oxide sedation should not be administered to infected patients.[47]

Patient and personnel should be education on sneeze/ cough etiquette.[56]

Shock waterlines.

-

Surfaces must be cleaned thoroughly after visits and routinely with Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) registered disinfectants.[45,57]

Clinic and office waste accumulation should be avoided; suspected SARS-CoV-2 waste should be disposed of using double-layer yellow medical waste bags and “gooseneck” ligation.[5,8]

-

Providers and personnel should be tested regularly.[59]

Personnel should receive flu vaccine.[60]

-

If patient has respiratory symptoms, provide mask and immediately isolate.

Defer treatment for at least 14 days and recommend self-quarantine.[5]

Report any cases to local health authorities.[60]

The American Association of Orthodontists also listed recommendations. Emergency situations must first be assessed by phone or video calls to triage patients.[61] Orthodontic practices typically have a pool of pediatric patients; considering that the pediatric population can be asymptomatic carriers of the virus, a key factor determining the ability to reopen should be the availability of personal protective equipment and access to acquiring more. It is recommended to order PPE for a 2-week period or longer as delivery times have been extended. Upon reopening, clinics should restart equipment, perform spore test sterilizer, test ultrasonic and instrument washer, shock waterlines, and train employees on proper PPE guidelines.[62]

The ADA also recommends phone screening before scheduling patients. Patients who have been infected with or have symptoms consistent with the coronavirus should not be seen until at least 7 days have passed since onset of symptoms, 3 days have passed since the patient is no longer symptomatic and not using fever reducing medications, or when the patient has negative test results.[63]

The Australian Society of Orthodontists makes similar recommendations as listed above. An additional recommendation is that upon continuation of routine care, providers should consider making appointments over the phone once the patient has left the practice to reduce in-office interactions. This society also recommends telling patients to bring their own glasses to wear at appointments to avoid cross-contamination.[64] The Bulgarian Orthodontic Society recommends making treatment systems passive to avoid frequent appointment visits, and sending patients accessories, and aligners through mail. They also recommend postponing removal of braces.[65] Moreover, according to the British Orthodontic Society, England has arranged local Urgent Dental Care[66] hubs that local practices refer their patients to during the pandemic, as all clinics have been told to stop providing care. These hubs are intended to treat patients with symptoms such as fractured teeth, post-extraction bleeding, facial swelling, and infections.[67]

The Egyptian Orthodontic Society recommends using hand sanitizer containing greater than 70% alcohol concentration before and after treatment. This organization also notes that pre-procedural mouthwash may be beneficial, but stressed chlorhexidine as not effective.[68] The Asian Pacific Orthodontic Society (APOS) stressed the importance of technology to continue patient care and dental education; an APOS editorial mentioned that having access to office data on a home computer, and having video consultations can benefit both patients and providers.[69]

The recommended precautions given by the Indian Orthodontic Society (IOS) are similar to the guidelines of other countries. The IOS stressed the assessment of chair operatories, making sure that they are a minimum of 6 feet away. They also recommend that if an employee or patient reports a fever, they should not come in for at least 24 h after being fever free with no fever-reducing medications.[70] This varies from the US recommendation of 3 days by the ADA. There should also be a daily screening log for employees to log temperature and symptoms.[71]

Another aspect to consider is contact tracing. In the May 8 UCSF SARS-CoV-2 Response Town Hall,[72] Dr. Mike Reid from the division of HIV, ID, Global Medicine and Center for Global Health Diplomacy, Delivery, and Economics at UCSF, stressed the importance of contact tracing; tracking the contacts of diagnosed cases, and notifying those individuals to self-quarantine. This a large-scale measure, as it requires training individuals to identify an estimated 3–4 individuals per case before reopening states, after which may increase. It is also important to pair contact tracing with available resources for the populace to be able to quarantine. In San Francisco, this has been practiced through providing motel rooms for the homeless demographic. It is also important to mobilize individuals of various cultural backgrounds who speak different languages and can effectively communicate to minority populations. Digital tools such as mobile applications can be a large player in contact tracing efforts.[73] An example of this is in Israel where the Ministry of Health introduced a mobile application called HAMAGEN to trace contacts to identify suspect patients and prevent transmission.[47]

There should also be a significant change in waiting room etiquette. Social distancing parameters may be installed, or patients may be required to remain in their vehicles and called in when the provider is ready to see them. Patients should bring their own masks to their appointment. All items in waiting rooms, such as magazines, will be removed. Proper signage reminding patients to practice hand hygiene will be posted on clinic walls. Plexiglass partitions may be installed for reception areas.[44,71] Another consideration is to minimize the number of patients scheduled at once.[63] This may have significant financial implications for orthodontists. There may also be a decline in patients seeking traditional orthodontics, and an increase in direct to consumer orthodontic options that significantly minimize and in most circumstances do not require any social interaction.

Dentists are also concerned about the changes necessary for infection control, thinking it may not be affordable and may affect treatment fees in the long run.[74] An increase in treatment fees for patients at university-based clinics due to increase in costs for adequate infection control can result in narrower patient populations. If patients are required to pay more, they may elect not to receive care which can impact orthodontic residents’ ability to start new cases.

The distribution of protocol themes referenced in [Figure 3] displays the emphasis put on PPE and change in PPE protocol as a result of SARS-CoV-2. Other heavily referenced themes were pre-treatment screening recommendations such as a call for telemedicine, questionnaires, and temperature checks, social distancing recommendations, disinfection/ sterilization, and hand hygiene. As illustrated by [Figure 3], there are a variety of different themes for health and safety of providers and patients in orthodontic practices. This scoping review serves as a preliminary guide. As time progresses and more studies are conducted on SARS-CoV-2 to show which interventions significantly protect against transmission, a more concrete guide can be solidified.

This review also has limitations. We did not assess the quality of the included literature because of the few types of articles available due to the novelty and changing circumstances of SARS-CoV-2. We only included literature available in English. Furthermore, because guidelines are constantly changing, this scoping review serves as a bank of current knowledge and a foundation to build on.

CONCLUSION

SARS-CoV-2 has had significant implications on global clinical guidelines and orthodontic education. Recommendations for infection control have become more rigorous due to the contagious nature of SARS- CoV-2. Orthodontic societies worldwide currently have similar guidelines for provider and patient safety. As dental institutions begin to reopen, additional consequences for patients, students, faculty, and providers will be unveiled. This scoping review provides an overview of the current guidelines available for orthodontists worldwide and calls for a more cohesive and uniform global clinical guidelines, and a more in depth review of impacts on orthodontic education.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as patients identity is not disclosed or compromised.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- A review of coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) Indian J Pediatr. 2020;87:281-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO COVID-19 Dashboard. Available from: https://www.covid19.who.int [Last accessed on 2020 May 04]

- [Google Scholar]

- WHO Director-general's Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID-19-11. 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 [Last accessed on 2020 May 04]

- [Google Scholar]

- Personal protective equipment and Covid 19-a risk to healthcare staff? Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2020;58:500-2.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Being a front-line dentist during the covid-19 pandemic: A literature review. Maxillofac Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;42:12.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COVID-19: Present and future challenges for dental practice. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:E3151.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- What dentists need to know about COVID-19. Oral Oncol. 2020;105:104741.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coronavirus COVID-19 impacts to dentistry and potential salivary diagnosis. Clin Oral Investig. 2020;24:1619-21.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scoping studies: Should there be more in orthodontic literature? APOS Trends Orthod. 2019;9:124-5.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The last decade in orthodontics: A scoping review of the hits, misses and the near misses? Semin Orthod. 2019;25:339-55.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Compliance monitoring via a Bluetooth-enabled retainer: A prospective clinical pilot study. Orthod Craniofac Res. 2019;22:149-53.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moving towards precision orthodontics: An evolving paradigm shift in the planning and delivery of customized orthodontic therapy. Orthod Craniofac Res. 2017;20:106-13.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:467-73.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical implications of the COVID-19 pandemic on dental education. J Dent Educ. 2020;84:512.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COVID-19-future of dentistry. Indian J Dent Res. 2020;31:167-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COVID-19: Perspective of a dean of dentistry. JDR Clin Transl Res. 2020;5:211-3.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COVID-19: The immediate response of European academic dental institutions and future implications for dental education. Eur J Dent Educ. ;2020

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Response to the letter to the editor: How to deal with suspended oral treatment during the COVID-19 epidemic. J Dent Res. ;2020 [Published on 2020 Apr 13]

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tele(oral)medicine: A new approach during the COVID-19 crisis. Oral Dis 2020:1-2. [Published on 2020 May 11]

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Available from: https://www.ada.org/~/media/CODA/Files/ORTHO_Flexibility_4_20.pdf?la=en [Last accessed on 2020 May 29]

- Impact of COVID-19 on dental education in the United States. J Dent Educ 2020:1-5. [Published on 2020 Apr 10]

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2020 Updated Written Exam Process. Available from: https://www.americanboardortho.com/orthodontic-professionals/about-board-certification/written-examination/2020-updated-written-exam-process [Last accessed on 2020 May 01]

- [Google Scholar]

- Response of the Dental Education Community to Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) Available from: https://www.adea.org/COVID19-Update [Last accessed on 2020 May 01]

- [Google Scholar]

- 6.6 Million More Americans File for Unemployment Amid COVID-19 Financial Crisis. ABC News. Available from: https://www.abcnews.go.com/Business/66-million-americans-file-unemployment/story?id=70061717 [Last accessed on 2020 May 01]

- [Google Scholar]

- Are dental schools adequately preparing dental students to face outbreaks of infectious diseases such as COVID-19? J Dent Educ. 2020;84:631-3.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health services provision of 48 public tertiary dental hospitals during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Clin Oral Investig. 2020;24:1861-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The novel coronavirus and challenges for general and paediatric dentists. Occup Med. 2020;kqaa055 [Published on 2020 May 02]

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical orthodontic management during the COVID-19 pandemic. Angle Orthod. ;2020 [Published on 2020 Apr 27]

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Precautions and recommendations for orthodontic settings during the COVID-19 outbreak: A review. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. ;2020 [Published on 2020 May 13]

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The impact of the COVID-19 infection in dentistry. Exp Biol Med 2020:1-5. [Published on 2020 May 21]

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overview of transnational recommendations for COVID-19 transmission control in dental care settings. Oral Dis 2020 [Published on 2020 May 19]

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Dentistry during the COVID-19 epidemic: An Italian workflow for the management of dental practice. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:3325.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COVID-19 outbreak: Succinct advice for dentists and oral healthcare professionals. Clin Oral Investig 2020:1-7. [Published on 2020 May 19]

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COVID-19: A novel coronavirus and a novel challenge for oral healthcare. Clin Oral Investig. 2020;24:2137-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Why re-invent the wheel if you've run out of road? Br Dent J. 2020;228:755-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Characteristics in children and considerations for dentists providing their care. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2020;30:245-50.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Management of orthodontic emergencies during 2019-NCOV. Prog Orthod. 2020;21:10.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS CoV-2) in dentistry. Management of biological risk in dental practice. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:3067.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Role of respirators in controlling the spread of novel coronavirus (Covid-19) among dental health care providers: A review. Int Endod J. ;2020 [Published on 2020 May 01]

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/cases-in-us.html [Last accessed on 2020 May 04]

- [Google Scholar]

- Dental care and oral health under the clouds of COVID-19. JDR Clin Transl Res. 2020;5:202-10.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safety guidelines for sterility of face shields during COVID 19 pandemic. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2020:1-2. [Published on 2020 Apr 30]

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Infection control in dental health care during and after the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak. Oral Dis 2020:1-10. [Published on 2020 May 11]

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Transmission routes of 2019-nCoV and controls in dental practice. Int J Oral Sci. 2020;12:9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidelines for dental care provision during the COVID-19 pandemic. Saudi Dent J. 2020;32:181-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dental care during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak: Operatory considerations and clinical aspects. Quintessence Int. 2020;51:418-29.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resources. Jackie Dorst. Available from: http://www.jackiedorst.com/resources [Last accessed on 2020 May 05]

- [Google Scholar]

- Possible aerosol transmission of COVID-19 and special precautions in dentistry. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2020;21:361-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biological and social aspects of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) related to oral health. Braz Oral Res. 2020;34:e041.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COVID-19 outbreak: An overview on dentistry. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:E2094.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19): Implications for clinical dental care. J Endod. 2020;46:584-95.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Immunocompromised patients and coronavirus disease 2019: A review and recommendations for dental health care. Braz Oral Res. 2020;34:e048.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strategies for prevention of coronavirus disease 2019 in the dental field. Oral Dis. ;2020 [Published on 2020 Apr 18]

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COVID-19 transmission in dental practice: Brief review of preventive measures in Italy. J Dent Res 2020:1-9. [Published on 2020 Apr 17]

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dental considerations after the outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus disease: A review of literature. Arch Clin Infect Dis 2020:e103257. [Published on 2020 Apr 14]

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- List N: Disinfectants for Use Against SARS-CoV-2. 2020. US EPA. Available from: https://www.epa.gov/pesticide-registration/list-n-disinfectants-use-against-sars-cov-2 [Last accessed on 2020 May 05]

- [Google Scholar]

- Recommendations for a safety dental care management during SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2020;44:e51.

- [Google Scholar]

- COVID-19: Its impact on dental schools in Italy, clinical problems in endodontic therapy and general considerations. Int Endod J. 2020;53:723-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Editorial: Dental practitioners' role in the assessment and containment of coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Evolving recommendations from the centers for disease control. Quintessence Int 1985. 2020;51:349-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- Protecting dental manpower from COVID 19 infection. Oral Dis 2020:1-4. [Published on 2020 May 13]

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COVID-19. AAO. Available from: https://www.aaoinfo.org/covid-19 [Last accessed on 2020 May 06]

- [Google Scholar]

- ADA Interim Guidance for Minimizing Risk of COVID-19 Transmission Bengaluru: Aeronautical Development Agency; [Published on 2020 Apr 01]

- [Google Scholar]

- COVID-19 Suggestions from ASO Members-Australian Society of Orthodontists. Available from: https://www.aso.org.au/covid-19-suggestions-aso-members [Last accessed on 2020 May 01]

- [Google Scholar]

- Bulgarian Orthodontic Society. Available from: https://www.blgos.org/?id=336 [Last accessed on 2020 May 05]

- [Google Scholar]

- Dentists Have 'Nowhere to Send Patients. BBC News. Available from: https://www.bbc.com/news/health-52197788 [Last accessed on 2020 May 01]

- [Google Scholar]

- British Orthodontic Society COVID19 BOS Advice Orthodontic Provider Advice Advice for Orthodontic Practices in Primary Care Settings. Available from: https://www.bos.org.uk/COVID19-BOS-Advice/Orthodontic-Provider-Advice/Advice-for-Orthodontic-Practices-in-Primary-Care-Settings [Last accessed on 2020 May 01]

- [Google Scholar]

- Guidelines for Corona Virus Safety. Available from: https://www.egyptortho.org/home_crona/Guidelines%20for%20Corona%20Virus%20safety.pdf [Last accessed on 2020 May 05]

- [Google Scholar]

- Indian Orthodontic Society. Available from: https://www.iosweb.net [Last accessed on 2020 May 01]

- [Google Scholar]

- COVID-19-control and Prevention. Denstistry Workers and Employers Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Available from: https://www.osha.gov/SLTC/covid-19/dentistry.html [Last accessed on 2020 May 05]

- [Google Scholar]

- UCSF COVID-19 Response Town Halls. Available from: https://www.ucsfhealth.mediasite.com/Mediasite/Catalog/catalogs/ucsf-town-hall [Last accessed on 2020 May 12]

- [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Get and Keep America Open. 2020. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/php/open-america/contact-tracing.html [Last accessed on 2020 May 12]

- [Google Scholar]

- Proposed Clinical Guidance for Orthodontists and Orthodontic Staff Post COVID-19 a Clinician's Perspective United States: American Association of Orthodontists; 2020.

- [Google Scholar]

APPENDIX A: SEARCH STRATEGIES

PubMed

#1

coronavirus [mh] OR coronavirus OR “COVID-19” OR “SARS-CoV-2” OR “severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2”[nm]

#2

(“dental education” OR “education, dental” [mh] OR orthodontics/education [mh] OR (orthodontics AND education))

#3

orthodontics [mh] OR orthodontics OR orthodontist [mh] OR orthodontist OR orthodontists OR dental care/methods [mh] OR “dental care” [tiab] OR dental clinics [mh] OR dentists [mh] OR dentist OR dentistry [mh] OR dentistry [tiab] OR “dental practice”

#4

Clinical Protocols [mh] OR protocol OR protocols OR practice guidelines as topic [mh] OR guidelines OR guideline OR recommendation OR recommendations OR recommended OR standards

#5

#1 AND #2

#

#1 AND #3 AND #4

#7

#5 OR #6