Translate this page into:

Body dysmorphic disorder in adult orthodontic treatment candidates according to the index of treatment need

*Corresponding author: Aydin Pirzeh, National Research Institute of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (NRITLD), Masih Daneshvari Hospital, Tehran, Iran. ap4177@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Shiazi M, Tofangchiha M, Taheri A, Pirzeh A. Body dysmorphic disorder in adult orthodontic treatment candidates according to the index of treatment need. APOS Trends Orthod. doi: 10.25259/APOS_183_2023

Abstract

Objectives:

Body image perception plays an important role in seeking orthodontic treatment. Body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) is a psychological condition where an individual constantly focuses on flaws in their appearance. This study aimed to assess BDD in adult orthodontic treatment candidates according to the index of treatment need (IOTN) in Qazvin city in 2020.

Material and Methods:

This descriptive study was conducted on 404 eligible patients over 18 years of age presenting to dental clinics in Qazvin seeking orthodontic treatment. The patients were categorized according to their IOTN (grades 1–5) and filled out the Body Deformation Metacognition Questionnaire (BDMCQ). Data were analyzed by t-test and Analysis of Variance using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences.

Results:

Of all the patients, 50.2% were grade 1 (no need for treatment),and 1.5% were grade 5 (very great need for treatment). Furthermore, 54.5% of patients had severe BDD. BDD had no significant correlation with gender or marital status (P > 0.05). BDD was significantly correlated with age, educational level, and IOTN grade (P < 0.05).

Conclusion:

The present results revealed that over 50% of patients seeking orthodontic treatment did not need treatment, according to the IOTN. Dental clinicians are advised to be more careful in accepting patients with a history of psychological problems and numerous surgical procedures who seek cosmetic treatments.

Keywords

Orthodontics

Index of orthodontic treatment need

Body dysmorphic disorder

INTRODUCTION

Crowded and protruded teeth have long been a problem for many individuals, and attempts to correct them date back to at least 1000 years before Christ.[1] The prevalence of dentofacial anomalies is approximately 82% in the United States, 78% in some parts of Europe,such as Finland, Switzerland, Denmark, and Sweden, 84% in parts of Iran, and 86% in Ahwaz, Iran, as reported in the literature.[2] With the advances in civilization, the prevalence of dentofacial anomalies, known as malocclusion, has increased similar to the prevalence of many other conditions such as hypertension, cardiovascular diseases, and diabetes mellitus. However, this increase in frequency does not mean that malocclusion is a normal phenomenon.[3]

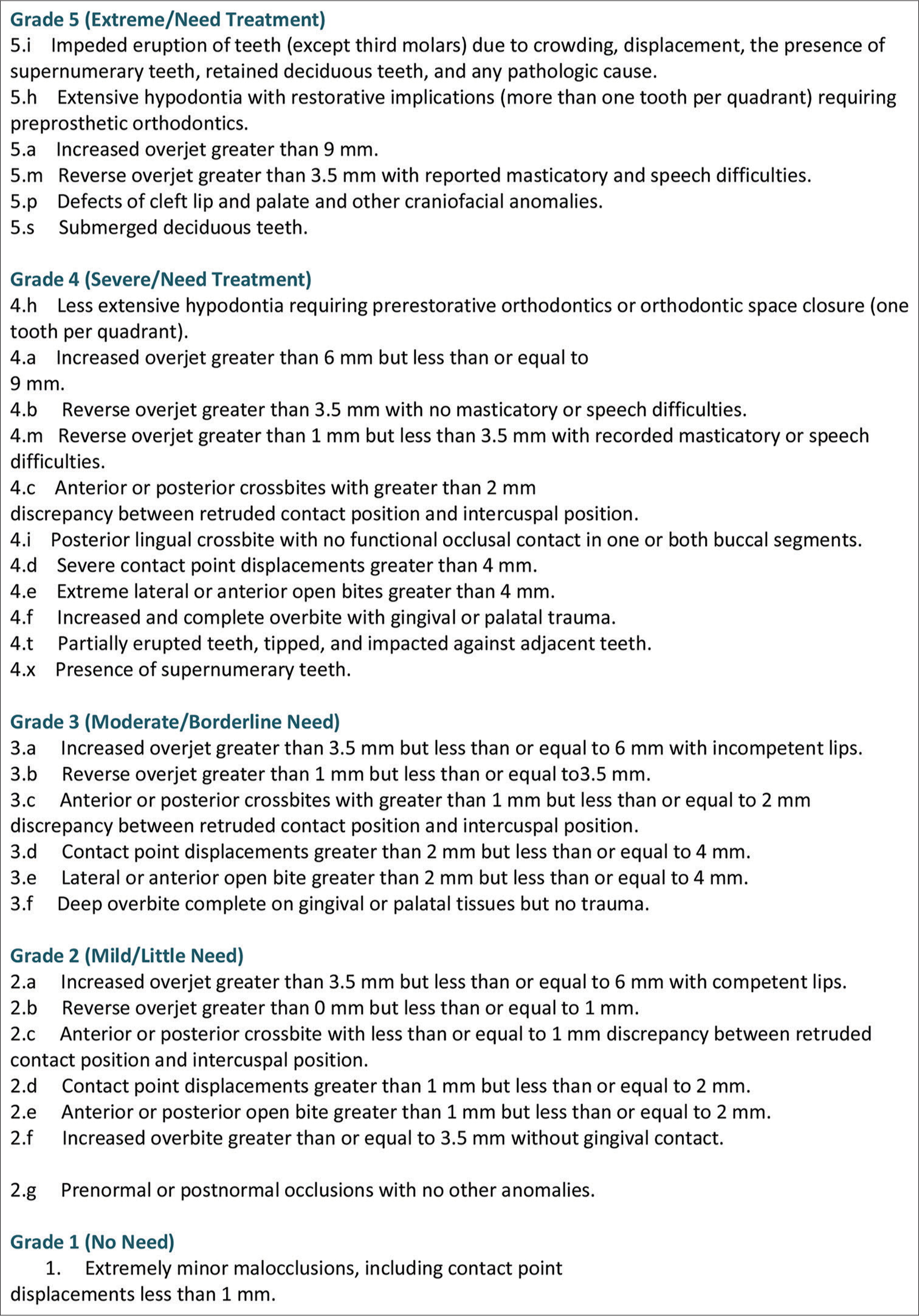

Index of treatment need (IOTN)

The Index of Treatment Need (IOTN), developed by Brook and Shaw in the United Kingdom,was designed to evaluate need for treatment. It places patients in five grades from “no need for treatment” to “treatment required” that correlate reasonably well with clinician’s judgments of need for treatment. The index has a dental health component derived from occlusion and and an esthetic component derived from comparison of the dental appearance versus standard photographs.[4] IOTN is a patient-driven index, which is a combination of one’s judgment about their attractiveness and assessment of esthetics using clinical indices.[5] IOTN is close to clinical judgment and is increasingly used since it addresses the severity of malocclusion while taking into account the esthetic parameters.[6] IOTN is commonly used worldwide for assessment of the need for orthodontic treatment.[7-10]

Body dysmorphic disorder (BDD)

Concerns about appearance are a well-accepted aspect of human behavior in most cultures. Nonetheless, obsession with such concerns with adverse effects on the quality of life may indicate body dysmorphic disorder (BDD). Although BDD was first described by Enrico Morselli, an Italian psychologist over 100 years ago and coined “dysmorphophobia” from the Greek term “dysmorphia” that means ugliness, evidence shows that it has not yet been well elucidated.[11] Not detecting BDD can bring about adverse physical and psychological consequences for patients and can lead to chronicity of this condition.[12]

The Fifth Edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders by the American Psychological Association describes BDD as “a preoccupation with one or more perceived defects in appearance that are not observable to others.”[13] The 11th Revision of the International Classification of Diseases 11 by the World Health Organization, which was recently published,statesthat BDD are such those patients who do not often have a correct attitude toward the main problem and, therefore, seek non-psychological treatments such as skin treatments, cosmetic procedures such as liposuction and rhinoplasty, and dental treatments such as tooth bleaching, orthodontic treatment, and maxillofacial surgery.[14] Since such patients do not have a correct attitude toward their psychological problem that is BDD, they are often dissatisfied with the results and undergo multiple procedures.

The number of individuals who seek orthodontic treatment to overcome psychosocial problems related to their facial appearance has increased in the recent years. Furthermore, more attention is paid to dental esthetics and facial appearance as novel goals in orthodontic treatment.[6] Recent evidence suggests that severe malocclusion can be considered as a social disability. Leveled and aligned teeth and a beautiful smile highly contribute to one’s self-esteem in social encounters,while crowded and protruded teeth often create a negative impression.[15]

BDD is a psychological condition where an individual constantly focuses on flaws in their appearance. Individuals with BDD are highly ashamed of flaws that are insignificant or even unnoticeable to others and experience a lot of stress and tension. Thus, they often avoid social encounters. It appears that the head and face are the most concerning body parts in patients with BDD. BDD is a rare condition; however, it can have a negative impact on orthodontic treatment. Patients with BDD are likely to seek orthodontic treatment, which is often associated with orthognathic surgery. However, such treatments rarely improve the perception of such patients about their flaws. Therefore, it is highly important for orthodontists to use screening tools for detection of BDD.[16] Thus, this study aimed to assess BDD in adult orthodontic treatment candidates according to the IOTN in Qazvin city in 2020.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Qazvin University of Medical Sciences with ethical number of IR.QUMS.REC.1400.088. There is no conflict with ethical considerations. This study was conducted on adult patients seeking orthodontic treatment in Qazvin city, Iran. Patients who could not fill out the questionnaire due to syndromes or cognitive impairments (such as Down syndrome and autism) were excluded from the study. Patients over 18 years of age presenting to dental clinics and offices in Qazvin city seeking orthodontic treatment who were willing to participate in the study were enrolled after obtaining their informed consent. They filled out the BDD questionnaire and were then examined by the same specialist. A tongue blade, a ruler (to measure the overbite and overjet), and disposable gloves were used for this purpose. The patients were assigned to IOTN grades 1–5 based on the dental health component (DHC) of IOTN [Figure 1]. Information of each patient was recorded in a checklist. The checklist included demographic information, IOTN grade, and the questionnaire score.

- Index of treatment need chart.

For assessment of DHC, overbite, occlusal interferences, overjet, cross-bite, semi-erupted teeth, missing teeth, cleft lip and palate, problems in deglutition, and tissue trauma are evaluated.[6] The order of assessment of the abovementioned factors is not important. The important topic is that the most severe malocclusion pattern is considered to make a decision about the need for treatment. Each group has subgroups that are marked with alphabets for epidemiological purposes.[17]

The AC includes 10 grades, characterized by 10 images. The images have been selected and classified by a group of dentists based on their attractiveness. This classification is based on dental attractiveness and not morphological similarities. The final score determines the need for orthodontic treatment based on esthetics and the psychosocial need for treatment. IOTN can be easily used by children and their parents, and there is a high agreement between the scores of dentists and parents.[3]

These two components are closely correlated. Thus, only the DHC was evaluated in this study. DHC evaluates 10 discrepancies, including overjet, reverse overjet, overbite, open bite, cross bite, crowding, tooth impaction, cleft lip/palate, buccal occlusion (class II and III), and hypodontia. This index has five grades, and each patient is assigned to one of them depending on the type of dental anomaly.[18]

The patients filled out the Body Dysmorphic Meta-Cognition Questionnaire (BDMCQ), and the results were recorded, coded, and used anonymously. To prevent bias, the researcher who analyzed the results was not aware of the contents of the questionnaire.

Study population and sample size

The samples were enrolled by convenience sampling. Since the prevalence of BDD was estimated to be 6.3% in the previous studies, the sample size was calculated to be 404, assuming 5% error and 95% confidence interval.[19]

Data collection and statistical analysis

The questionnaires were collected and the data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 24. Descriptive results were reported as frequency, mean, and standard deviation depending on the type of variable and statistically analyzed by the correlation tests, t-test, and Analysis of Variance (ANOVA).

RESULTS

Based on the ANOVA statistical test, a significant relationship was observed between BDD severity and IOTN grade in the participants (P < 0.05). 56.4% of women and 44.9% of men have BDD disorder. 54.5% of adults seeking for orthodontic treatment have BDD disorder. Furthermore, based on the T test, there was no significant relationship between the prevalence of BDD and the gender and marital status of the patients (P < 0.05). About 93.3% of participants that were over the age of 41 have severer BDD disorder, while this ratio is 14.5% for people under the age of 20. Based on the statistical correlation test, a significant relationship was observed between the prevalence of BDD and the age of the patients (P < 0.05). Furthermore, based on the ANOVA statistical test, a significant relationship was observed between the level of education and the prevalence of BDD in the patients (P < 0.05) [Tables 1-9].

| Category | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Age groups | ||

| <20 years | 62 | 15.3 |

| 21–30 years | 175 | 43.3 |

| 31–40 years | 137 | 33.9 |

| >41 years | 30 | 7.4 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 335 | 82.9 |

| Male | 69 | 17.1 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 294 | 72.8 |

| Married | 110 | 27.2 |

| Level of education | ||

| Under high-school diploma | 47 | 11.6 |

| High-school diploma | 172 | 42.6 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 108 | 26.7 |

| Master’s degree and higher | 77 | 19.1 |

| IOTN | BDD | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild | Moderate | Severe | ||

| 1 | 0.000 | |||

| Frequency | 2 | 9 | 192 | |

| Percentage | 1.0 | 4.4 | 94.6 | |

| 2 | ||||

| Frequency | 17 | 14 | 3 | |

| Percentage | 50.0 | 41.2 | 8.8 | |

| 3 | ||||

| Frequency | 23 | 16 | 2 | |

| Percentage | 56.1 | 39.0 | 4.9 | |

| 4 | ||||

| Frequency | 54 | 45 | 21 | |

| Percentage | 45.0 | 37.5 | 17.5 | |

| 5 | ||||

| Frequency | 3 | 1 | 2 | |

| Percentage | 50.0 | 16.7 | 33.3 | |

| Total | ||||

| Frequency | 99 | 85 | 220 | |

| Percentage | 24.5 | 21.0 | 54.5 | |

IOTN: Index of treatment need, BDD: Body dysmorphic disorder

| IOTN | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Grade | ||

| 1 | 203 | 50.2 |

| 2 | 34 | 8.4 |

| 3 | 41 | 10.1 |

| 4 | 120 | 29.7 |

| 5 | 6 | 1.5 |

IOTN: Index of treatment need

| BDD | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Severity | ||

| Mild | 99 | 24.5 |

| Moderate | 85 | 21 |

| Severe | 220 | 54.5 |

BDD: Body dysmorphic disorder

| Gender | BDD | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild | Moderate | Severe | ||

| Female | 0.778 | |||

| Frequency | 84 | 62 | 189 | |

| Percentage | 25.1 | 18.5 | 56.4 | |

| Male | ||||

| Frequency | 15 | 23 | 31 | |

| Percentage | 21.7 | 33.3 | 44.9 | |

| Total | ||||

| Frequency | 99 | 85 | 220 | |

| Percentage | 24.5 | 21.0 | 54.5 | |

BDD: Body dysmorphic disorder

| Marital status | BDD | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild | Moderate | Severe | ||

| Single | 0.235 | |||

| Frequency | 56 | 49 | 189 | |

| Percentage | 19.0 | 16.7 | 64.3 | |

| Married | ||||

| Frequency | 43 | 36 | 31 | |

| Percentage | 39.1 | 32.7 | 28.2 | |

| Total | ||||

| Frequency | 99 | 85 | 220 | |

| Percentage | 24.5 | 21.0 | 54.5 | |

BDD: Body dysmorphic disorder

| Age groups | BDD | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild | Moderate | Severe | ||

| <20 years | 0.000 | |||

| Frequency | 29 | 24 | 9 | |

| Percentage | 46.8 | 38.7 | 14.5 | |

| 21–30 years | ||||

| Frequency | 48 | 40 | 87 | |

| Percentage | 27.4 | 22.9 | 49.7 | |

| 31–40 years | ||||

| Frequency | 21 | 20 | 96 | |

| Percentage | 15.3 | 14.6 | 70.1 | |

| >41 years | ||||

| Frequency | 1 | 1 | 28 | |

| Percentage | 3.3 | 3.3 | 93.3 | |

| Total | ||||

| Frequency | 99 | 85 | 220 | |

| Percentage | 24.5 | 21.0 | 54.5 | |

BDD: Body dysmorphic disorder

| Level of education | BDD | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild | Moderate | Severe | ||

| Under high-school diploma | 0.001 | |||

| Frequency | 11 | 13 | 23 | |

| Percentage | 23.4 | 27.7 | 48.9 | |

| High-school diploma | ||||

| Frequency | 38 | 34 | 100 | |

| Percentage | 22.1 | 19.8 | 58.1 | |

| Bachelor’s degree | ||||

| Frequency | 39 | 27 | 42 | |

| Percentage | 36.1 | 25.0 | 38.9 | |

| Master’s degree and higher |

||||

| Frequency | 11 | 11 | 55 | |

| Percentage | 14.3 | 14.3 | 71.4 | |

| Total | ||||

| Frequency | 99 | 85 | 220 | |

| Percentage | 24.5 | 21.0 | 54.5 | |

BDD: Body dysmorphic disorder

| Being religious | BDD | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild | Moderate | Severe | ||

| Not religious | 0.071 | |||

| Frequency | 24 | 30 | 77 | |

| Percentage | 18.3 | 22.9 | 58.8 | |

| Religious | ||||

| Frequency | 36 | 25 | 84 | |

| Percentage | 24.8 | 17.2 | 57.9 | |

| Very religious | ||||

| Frequency | 39 | 30 | 59 | |

| Percentage | 30.5 | 23.4 | 46.1 | |

| Total | ||||

| Frequency | 99 | 85 | 220 | |

| Percentage | 24.5 | 21.0 | 54.5 | |

BDD: Body dysmorphic disorder

DISCUSSION

According to the present results, grade 1 IOTN had the highest prevalence (50.2%),followed by grade 4 (29.7%). This finding indicates that over half of the participants did not need orthodontic treatment, and this issue should be taken into account in their dental visit. Furthermore, over half of the participants had severe BDD. The present results revealed that a higher percentage of females (56.4%) compared with males (44.9%) had severe BDD. Greater attention of females to esthetics and their possible mental obsessions in this regard,as well as the public perceptions are probably responsible for this finding. Furthermore, single individuals had a higher frequency of severe BDD (64.3%) compared with married individuals (28.2%). This difference can be due to concerns and challenges encountered by singles. Moreover, a significant correlation existed between the prevalence of BDD, and theage of participants such that by an increase in age, the severity of BDD increased. A similar study[20] showed that younger individuals had a higher frequency of BDD, while in the present study, BDD was more common in older participants.

The present results revealed a significant correlation between the level of education and prevalence of BDD, such that the BDD score of participants with a Master’s degree or higher level of education was significantly higher than that of other educational groups. This finding can be due to the higher level of social interactions of such individuals and their need for higher self-esteem. A significant correlation was noted between the severity of BDD and degree of IOTN in the present study, such that the BDD score of the participants with grade 1 IOTN (not requiring treatment) was significantly higher than that of other individuals. In other words, individuals who did not require any treatment had a higher prevalence of BDD than others. Having religious beliefs had no significant correlation with the prevalence of BDD in the present study.

Devanna analyzed 1745 participants across five studies and reported that female patients with BDD were more interested in orthodontic treatment than male patients.[21] The same result was obtained in the present study, which can be due to the higher attention of females to esthetics and their obsessions with their attractiveness as well as the public opinion in this regard. Tusi et al. evaluated IOTN among medical students and reported that 8.3% of them had a moderate need for orthodontic treatment, according to the AC. Moreover, according to the DHC, 8.6% of students had a moderate need, and 0.8% had a severe need for orthodontic treatment. In total, the need for orthodontic treatment was relatively low in medical students of Alborz University of Medical Sciences.[17] In the present study, 8.4% of the participants had a mild, and 10.1% had a moderate need for orthodontic treatment, which was different from their results. This difference can be due to the fact that the present study was conducted on candidates for orthodontic treatment. Furthermore, the two studies were conducted in n different cities. Sathyanarayana et al. evaluated the prevalence of BDD in 1184 individuals over 18 years who sought orthodontic treatment. Of all, 62 individuals (5.2%) were positive for BDD; the majority of them were single and young and had many previous orthodontic consultations.[22] In the present study, 54.5% of the participants had severe BDD and 21% had moderate BDD, which was different from the results of Sathyanarayana et al.[22] Furthermore, unlike their study that reported a higher frequency of BDD in younger individuals, the present study showed an increase in the severity of BDD with age. This difference in the results may be due to cultural differences and different prevalence rates of the disease in the study populations, as well as differences in the treatment costs. Due to the low costs of orthodontic treatment in Iran, the number of patients seeking orthodontic treatment due to mild problems is often higher than that in other countries. Furthermore, the economic status and the referral system of other countries are such that only patients who truly need orthodontic treatment are referred to orthodontists, which can be another reason for different results obtained. However, the present findings regarding the marital status of patients were in agreement with their results. Etezadi et al. evaluated the orthodontic treatment need of 12-14-year-old students in Sari, Iran, and reported that of all, 24% had grade 1, 29.2% had grade 2 (small need for treatment), 21.5% had grade 3, 17.2% had grade 4, and 8.2% had grade 5 (very great need for orthodontic treatment).[23] These values were 50.2%, 8.4%, 10.1%, 29.7%, and 1.5%, respectively, in the present study, which are different from their results. This difference may be attributed to the evaluation of different age groups and study populations from two different cities. Gyawali et al. evaluated IOTN of 207 patients under orthodontic treatment and reported that 0.5% were grade 1, 9.7% were grade 2, 24.2% were grade 3, 46.9% were grade 4, and 18.8% were grade 5. The majority of such patients had a great and very great need for treatment while a small number of them (0.5%) did not need treatment.[24] Unlike their study, over half of the participants in the present study did not require any treatment, and only 1.5% had a great need for orthodontic treatment. This difference can be attributed to different study populations (patients seeking treatment and those already under treatment). Yassaei et al. evaluated the prevalence of BDD in 270 patients; out of which, 17 (5.5%) were positive for BDD; 80% of them had a history of multiple orthodontic treatments in the past, and the majority of them were single women and younger than BDD-negative individuals.[14] In the present study, over half of the participants (54.5%) had severe BDD, which was different from the results of Yassaei et al.[14] Furthermore, unlike their study, the severity of BDD increased with age in the present study, which can be due to differences in study populations since they evaluated patients referred by dentists for orthodontic treatment, which indicates their actual need for treatment while the present study was conducted on patients seeking orthodontic treatment by themselves. However, their results regarding marital status and gender were in agreement with the present findings.

Hepburn and Cunningham evaluated BDD in 70 adults presenting to the Orthodontics Department of Eastman Dental Hospital in London. BDD was diagnosed in 2 of the general population (2.86%) and three orthodontic patients (7.5%).[5] Their results were different from the present findings since over 50% of the participants had severe BDD in the present study. This difference may be due to the fact that their study was conducted on patients already under orthodontic treatment and the general population, and considering the referral system of patients in the UK, patients under treatment are those who actually need treatment.

CONCLUSION

Many cosmetic demands of individuals depend on their self-image. Some patients who seek orthodontic treatment for esthetic purposes may have a misleading image of themselves. The results showed that over half of the participants had no need for treatment according to their IOTN grade, and over half of them had severe BDD. Thus, orthodontists should be careful in admitting patients with a history of psychological and personality problems and a positive history of multiple cosmetic procedures and encourage such patients to seek psychological counseling or refer them to a psychologist to prevent adverse consequences.

Ethical approval

The research/study approved by the Institutional Review Board at Qazvin University of Medical Sciences, number IR.QUMS.REC.1400.088, dated May 26, 2021.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

References

- Evaluation of relationship between orthodontic treatment need according dental aesthetic index (DAI) and Student’s Perception in 11-14 year old students in the city of Ahwaz in 2005. J Mashhad Dent Sch. 2007;31:37-46.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bioarchaeology: Interpreting behavior from the human skeleton. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press; 1997. p. :105-7.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The development of an index for orthodontic treatment priority. Eur J Orthod. 1989;11:309-32.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Body dysmorphic disorder in adult orthodontic patients. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006;130:569-74.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orthodontic treatment need in 14-16 year-old Tehran high school students. Aust Orthod J. 2009;25:8-11.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Determination of needs for orthodontic treatment in 11-14 year-old students of Shiraz [Doctorate Thesis] Iran: Dental School of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences; 2003. Persian

- [Google Scholar]

- Determination of needs for orthodontic treatment in 12-13 year-old students of Gorgan [Doctorate Thesis] Iran: Dental school of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences; Persian

- [Google Scholar]

- Determination of needs for orthodontic treatment in 12-13 year-old students of Bandar Anzaly [Doctorate Thesis] Iran: Dental School of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences; 1999. Persian

- [Google Scholar]

- Body image, eating, and weight: A guide to assessment, treatment, and prevention Vol 201. (1st ed). Germany: Springer; p. :85-95.

- [Google Scholar]

- A 4-year prospective observational follow-up study of course and predictors of course in body dysmorphic disorder. Psychol Med. 2013;43:1109-17.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders In: Text revision (4th ed). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

- [Google Scholar]

- Body dysmorphic disorder in Iranian orthodontic patients. Acta Med Iran. 2014;52:454-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- The influence of children's dentofacial appearance on their social attractiveness as judged by peers and lay adults. Am J Orthod. 1981;79:399-415.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Body dysmorphic disorder: A guide to identification and management for the orthodontic team. J Orthod. 2018;45:163-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Investigation of IOTN index in students of Alborz university of medical sciences in 2018. AUMJ. 2020;9:23-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Understanding and treating body dysmorphic disorder. Indian J Psychiatry. 2019;61:131-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malocclusion as an etiologic factor in periodontal disease: A retrospective essay. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2001;120:112-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Two-Sided confidence intervals for the single proportion: Comparison of seven methods. Stat Med. 1998;17:857-72.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of body dysmorphic disorder in patients seeking orthodontic treatment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2021;11:1232-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of body dysmorphic disorder among patients seeking orthodontic treatment. Prog Orthod. 2020;21:20.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orthodontic treatment need in 12-14 year-old school students in Sari, Iran. J Mazand Univ Med Sci. 2019;29:91-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Index of orthodontic treatment need of patients undergoing orhodontic treatment at BPKIHS, Dharan. Orthod J Nepal. 2016;6:23.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]